Guatemalan Immigrant Kills a Family With a Hammer

Two incomplete, sun-whitened homo skeletons prevarication spoon-fashion below a drought-stunted palo verde tree in the Arizona desert. Animals—nigh likely pack rats, coyotes, and buzzards—have strewn ribs and vertebrae and other bones along a wide swath of biscuit sand. Scattered among the remains are a few Mexican coins, an orange rummage, a toothbrush, a short-sleeved polo shirt, a zero-upwardly blue jacket, a pair of jeans, a pair of blue panties and bra, a unmarried green sock, a crocheted collar adorned with simulated pearls and garnets, a royal and white backpack, and a complete set up of upper and lower fake teeth with a yellow metallic star on the right front tooth.

It's Feb 12, 2012, and Border Patrol agents stumble upon the grim scene while on a routine patrol about nine miles north of the Mexican line on the Tohono O'odham Nation reservation, about Sells, Arizona. The agents take a GPS reading and notify Detective Juan Gonzales of the Tohono O'odham Law Section, which has jurisdiction over the investigation of deaths on tribal lands. They then head back out into the unforgiving desert.

The following solar day, Detective Gonzales visits the death site. He cannot find any identification documents. In that location's no sign of foul play. He collects the basic and effects, places them in a white plastic trunk bag, and transports the packet to the Pima Canton Office of the Medical Examiner in Tucson, about 90 miles northeast.

Over the next few days, Pima Canton Chief Medical Examiner Gregory Hess analyzes the skeletons. Hess is an expert in performing autopsies like these—autopsies of people who are presumed to have died trying to illegally cross the border from Mexico. Indeed, his role examines more migrant remains than any other medical-examiner office in the land. When these remains amount to animal-scattered sun-bleached bones that may accept been in the desert for years, it is often incommunicable to determine how they died. In that location simply aren't enough clues. And and then, instead of focusing on the crusade of death, Hess aims to begin the long process of identifying the remains so that relatives seeking missing edge-crossers can have some measure of peace.

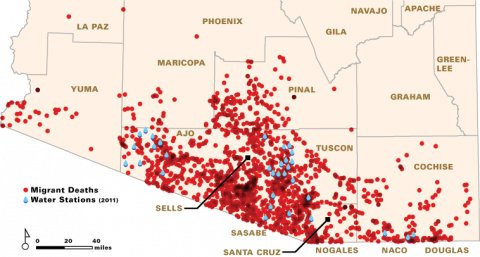

Hess works closely with forensic anthropologists, foreign consulates, and the Arizona-based human being rights group Derechos Humanos, all of which collect and tabulate reports from frantic relatives of missing undocumented border-crossers. His role also enters migrant-remains information into the National Missing and Unidentified Persons Organisation, and partners with Humane Borders—a group famous for placing h2o on treacherous migrant trails—to create a searchable map of migrant deaths in Arizona.

In this case, after Hess completes his autopsy on the bones delivered by Detective Gonzales, forensic anthropologist Angela Soler rebuilds the ii skeletons like puzzles, assigning stray ribs and femurs to the appropriate skulls. She determines that one skeleton belonged to a Hispanic adult female aged 45 to 65, who stood about 4 feet 10 inches tall. The simulated teeth with the ornamental star were likely hers. Soler can't make up one's mind the sex of the other person, but telltale molars and unfused basic indicate the skeleton belonged to a juvenile, aged x to 13.

Increased militarization of the border dissuades some crossers, but forces others to take more dangerous routes.

The two skeletons are labeled Doe 12-00360 and Doe 12-00359. A red plastic identification bracelet is hooked through the center socket of each skull. Os samples are excised for Deoxyribonucleic acid testing. Next, the skeletons are zipped into separate trunk bags and wheeled on a shiny metallic gurney to the foul-smelling refrigerated room where dozens of other migrant remains are stored on shelves. Sealed in plastic bags in humid weather condition, the bones begin to gather mold.

THE BORDER Patrol'south Tucson Sector, where the skeletons were found, is the nation's busiest and deadliest corridor for illegal clearing, covering 262 miles of the Arizona-Mexico line. The Tucson Sector is called the "Funnel" because heavy border enforcement in Texas and California has long funneled undocumented immigrants through Arizona. Now, heightened border security that began in the early 2000s in Arizona has created funnels within the Funnel, driving more than undocumented migrants away from urban crossings, and into parched desert terrain.

It has get commonplace for Border Patrol agents to discover remains of the dead in the Arizona desert. And a new written report by the Binational Migration Found at the University of Arizona—which looked at more than 2,000 deaths of undocumented border-crossers in the Arizona borderlands between 1990 and final year—found a correlation between the state's increased border enforcement over the past decade and migrant deaths. The reason is straightforward: increased militarization of the border may dissuade some undocumented immigrants from trying to get to the U.Southward., simply for the many undocumented crossers who are determined to come anyway, it simply forces them to take more dangerous routes.

The implications of this finding for the electric current immigration debate nether way in Washington are profound. It means that fifty-fifty more deaths along the border may exist one upshot of the clearing reform bill now being considered by the House. That pecker includes a $46.3 billion "border surge," which would farther militarize the Usa–United mexican states line, increasing the number of Edge Patrol agents from xviii,500 to 38,500, and adding 350 miles of debate to the 2,000-mile purlieus. The Congressional Budget Role estimates that this increased enforcement would reduce illegal immigration by 30 to fifty percent. But for those still gear up on coming to America illegally, the journey will be a lot more chancy. "If the past is an indicator of the hereafter," predicts Daniel Martínez, the lead author on the Binational Migration Institute study and a sociology professor at George Washington University, "increased edge enforcement will likely lead to more deaths on the edge."

The stories of those dead—who they were in life, why they took such extraordinary risks to come here—often get untold. And then information technology was for Doe 12-00360 and Doe 12-00359. At to the lowest degree at outset.

It'South 1978. On the twenty-four hours her grandmother disappears, Fermina Lopez Greenbacks is 12 years one-time and harvesting java at a large subcontract on the slope of a mountain in western Guatemala, well-nigh a small community called Tuibuj.

Fermina is a thin, small Mayan daughter with fiery black eyes and a shiny blackness complect that reaches down to her waist. Dressed in traditional Mayan clothes—an ankle-length cotton patterned skirt chosen a corte, a curt-sleeved smocklike blusa, and a brightly colored delantal, or frock—she's dwarfed past her big white coffee-edible bean handbag. Like most of the children she knows, she's illiterate. She attends school simply one time in a while, when she isn't needed to wash apparel in the river, or harvest, or make tortillas, or chop forest, or intendance for younger siblings.

On this day, as she picks the reddish fruit from java plants, she hears a truck pulling up to the family farm, where her grandmother Cipriana Chilel works the land. She hears the shouts of men, the roar of the truck as it travels down the mountain.

A encarmine internal conflict between the Guatemalan government and rebel guerrillas has been raging for close to two decades now; human rights abuses past the government are widespread. When Fermina and her mother, Maria Candelaria Greenbacks Chilel, render to Cipriana'due south house, where they live with their extended family unit, their relatives say army soldiers accused the old woman of giving the guerrillas food, and took her away in their truck. Terrified past the family matriarch'due south disappearance and the connected presence of soldiers in the expanse, Fermina's extended family abandons their land and scatters. Uncle Rufino Perez hides in the mountains, then escapes to Chiapas, Mexico. Fermina's male parent, Alberto Lopez, takes 1 son and daughter to United mexican states City. Fermina and her mother travel throughout western Republic of guatemala, harvesting sugar pikestaff, coffee, rice, and cotton fiber.

Mario José Ramirez, Fermina's grandfather, remains in the Tuibuj region. 2 years later, he disappears. Villagers say he was shot by soldiers and is cached in a mass grave in the mountains.

When she's 18, Fermina helps her mother buy a small piece of land in the poorest section of El Porvenir, a boondocks in San Marcos, a Guatemalan country that borders Chiapas, United mexican states. Fermina and her mother have worked side by side for years at present, and they're like sisters. They build a one-room wood-and-tin can shack with a clay floor on their land. They plant banana trees and coffee plants near the outdoor kitchen, a cooking fire and a shaded table a few steps away from the firm. For luck, they plant corn near the door.

But there is no luck. Fermina'south female parent and father have carve up up. One sister, Romelia, and a brother, Rosendo, live with Alberto. Another sister, Ana, dies of a mysterious breadbasket ailment. The two younger girls, Clarissa and Lucia, live with Fermina and their mother, Candelaria. Often, there is non enough nutrient. Fermina pines for the family farm in Tuibuj, which was taken over by another family after her grandparents disappeared.

A human being in El Porvenir tells Fermina he wants to marry her, then disappears after she gets pregnant. She's 23. Her son, Jorge, is a baby on the day Fermina's mother walks to the downtown marketplace with Clarissa. A car stops beside them. Men push Fermina's mother into the machine and drive off, leaving the child on the sidewalk.

Candelaria disappears in March 1989. Guatemala'south civil war has been raging for well-nigh three decades. The regular army sets up an encampment in El Porvenir, and villagers stay in their homes every bit much as possible.

Of the one million Guatemalans displaced by ceremonious disharmonize, several thousand sought safety in the United States.

Fermina and her sister Romelia walk to the military machine encampment and ask if their mother is detained in that location. "Was she a guerrilla?" a soldier asks. "She probably fed the guerrillas."

"She didn't feed the guerillas," Fermina says. "I know she isn't a guerrilla. I was with her every twenty-four hour period. All she does is piece of work."

The soldiers say they might find her mother if she pays them money. Fermina says she has no money. She goes to the police. They say they can't aid her.

Now she's got iii kids to take care of—two lilliputian sisters and her own infant. For months, she looks down the narrow dirt-and-rock street to see if her female parent is coming home.

DYING TO Cross

"Quit moping and looking downwards the street," another single mom tells Fermina. "Come have a drink with me." They share aguardiente, a powerful liquor made of sugarcane, and it helps Fermina forget about her female parent, if only for a few hours. Some days, she pulls out a movie of herself and her mother and Romelia, continuing in front of a tree with pink flowers. Information technology is her only photograph of her female parent, and she treasures information technology.

"Fermina works like a homo," the neighbors say. She cuts dry forest with a machete in the mountains some two kilometers from town, then hauls it to El Porvenir on her back, anchoring the load with a brow strap. There are days she has just salted tortillas for the kids to swallow.

Her father takes the trivial girls to live with him. Lonely with her toddler son, Jorge, Fermina falls in love with a married man. She has two more children—get-go Veronica, then Nelson Omar, who is born in April 1997 on the street most the plaza in El Porvenir because Fermina can't finish the long hike to the midwife's house.

THE Yr Fermina becomes pregnant with Omar, 1996, the Guatemalan government and the Guatemalan National Revolutionary Unity (the guerrillas) sign a peace treaty. 1 of the longest civil conflicts in Latin America officially ends. 3 years after, the Commission for Historical Clarification, an investigative group canonical past both the guerrillas and the government, issues a human rights report. It estimates that 200,000 people died in the confrontation, including 40,000 "disappearances."

The commission makes clear the culpability of the Us in helping fuel this crime against humanity. Washington, which had ousted Guatemala's elected president Jacobo Arbanz in 1954, periodically provided military help to subsequent anti-communist Guatemalan governments, enabling their brutality. In the words of the commission, U.S. assistance was "directed towards reinforcing the national intelligence appliance and for training the officer corps in counterinsurgency techniques, central factors which had a significant bearing on human being rights violations during the armed confrontation."

While guerrillas committed some "vehement and extremely roughshod acts," the report finds that the Guatemalan government and its paramilitary groups were responsible for 93 percent of the documented human rights violations during the conflict, including 92 percent of the arbitrary executions and 91 percent of the forced disappearances. The commission also notes that "the vast majority" of human rights victims were Mayans who were identified by the government as "guerrilla allies."

In the years that follow, groups like the National Security Annal in Washington uncover boosted documents that support the commission'southward written report on human rights violations. "There was wholesale targeting of Mayans in some areas of the highlands," says Kate Doyle, a senior annotator with the National Security Archive. The conflict created "massive human movements" among the "totally marginalized poor."

WITH HER three kids in tow, Fermina at present travels back and forth between Peronia, a slummy suburb of Republic of guatemala City where she builds a shack and sells tortillas, and El Porvenir, where she harvests coffee and sees the husband she loves. The father of Veronica and Omar is poor and has his own married woman and children to care for. Occasionally he gives Fermina money, simply it is never enough. The coffee harvest lasts only 3 months, and she earns most $270 total. She clears about $three each day selling tortillas in Guatemala City. With this, she feeds and dresses her kids, pays housing expenses, buys schoolhouse supplies and uniforms. Jorge completes sixth form. Veronica is needed at home and drops out in third. Omar, she vows, will stay in schoolhouse every bit long as possible.

The long civil state of war has unleashed a culture of violence, and the murder rate continues to climb later on the peace treaty is signed. A gang called M-xviii extorts money from Guatemala City slum shopkeepers for "protection" and kills those who don't pay.

Fermina hasn't prayed for years. Only in the slum, evangelicals convince her God is good, and promise a glorious heaven for truthful Christians. Eventually she converts. She quits drinking and breaks upward with the father of Veronica and Omar.

Omar is Fermina's favorite child. He'due south a placid, tiny child with large blackness eyes. He's docile and obedient. If it'due south raining and the clay floor is dirty, Fermina tells Omar to sit on the bed and not get off until the flooring dries, and he obeys. She hits her other two kids when they disobey, just she has never hit Omar.

Each fourth dimension she returns from Peronia to El Porvenir, she sees changes. Of the one million Guatemalans displaced by ceremonious conflict, several thousand sought safety in the United States. Villagers from El Porvenir settled in Arizona and Pennsylvania, and poverty-stricken friends and family unit members accept afterwards joined them.

Bigger houses with indoor plumbing and several rooms begin to sprout up on the hilly streets of El Porvenir, the structure bankrolled past remittances from family unit members in Philadelphia and Phoenix. Often, it takes years to finish the houses, and family members live in them even though rebar reaches into the sky, or block walls await completion. In El Porvenir, the locals call it "remittance architecture."

A sign at the Guatemalan consulate warns, 'Every day, three people die on the border and it's never the coyote.

Remittance architecture is a testament to the American Dream, and in the spring of 2006, Fermina decides to drift to the United States, salve enough coin to purchase land in Republic of guatemala, and render home. She figures she can ship money to the kids, and they tin have care of themselves in Peronia. Jorge is 17 and working construction in Guatemala City. Veronica is 13 and able to intendance for Omar, who is nine. Fermina cuts a deal with a neighbour in Peronia: the neighbor and Veronica volition brand and sell tortillas when Omar is in schoolhouse. Between that income and Jorge's structure job and remittances from Fermina, she's not worried near the kids. If they don't similar living in Peronia they can motion in with friends or relatives in El Porvenir. She won't be long in the United states of america; she just wants to save money, then return to Republic of guatemala to purchase land equally rich as the family subcontract in Tuibuj.

Another neighbor, Edelmira, who has crossed into the United states illegally several times, lends Fermina $five,000 at x percent involvement per annum to pay the smuggler. When Fermina leaves for the United States on a spring day in 2006, the older kids know of her plans. But Fermina tells Omar she'south just going down to the store and will be right back considering she doesn't desire him to cry.

FERMINA KNOWS Cardinal American migrants are preyed upon in Mexico, so she tries to appear Mexican. In Tapachula, just across the border from Guatemala, she abandons her traditional, comfortable Mayan clothes for the first time in her life. She changes into a Ladino outfit—a knee-length brim and T-shirt. She buys fraudulent documents that say she is a Mexican citizen.

Careful not to speak and betray her Mayan roots via her heavily accented Spanish, she travels several days by motorcoach to Altar, Sonora, a few miles south of the Arizona edge. Altar is a staging area for the long desert crossing; human smugglers assemble their client groups here. She meets a coyote and embarks on a journey through the desert. She has no idea where she is. Ayúdame Diosito. Help me God, she prays. The grouping hikes about 10 miles each night and sleeps in the twenty-four hours to avert the Border Patrol. She tries to conserve her gallon of h2o and refills it from a few mud puddles, merely she is always very thirsty. She prays for strength to keep up with the guide. On the morning of the fifth day, the group arrives at a paved route, climbs into a vehicle, and travels about 100 miles northeast to Phoenix.

Edelmira's sons pay the coyote for Fermina's passage. Fermina will stay nigh the sons for one year until she pays off her debt to Edelmira.

She settles in a Guatemalan neighborhood in a poor district of central Phoenix. In that location are Guatemalan food stores, evangelical churches, and restaurants. Whole apartment buildings are rented by Guatemalan immigrants—iv can share rent for a one-bedroom apartment.

Non long after she arrives, Fermina falls in dearest. Florentin Zaccharias lived in the highlands higher up El Porvenir, and he and Fermina knew each other when they were kids. He's left backside a wife and two children. He works in a juice factory, sends monthly remittances abode, and is a devoted evangelical. He's gentle with Fermina, comforts her, respects her, talks to her for hours. They are then far from Guatemala, what could be the harm in their relationship?

Fermina works part-fourth dimension jobs—she delivers telephone books for $3.80 hourly, paints piece of furniture for $7.25 hourly, irons tablecloths and sheets at a professional laundry for $7.35 hourly, and sells homemade tamales on weekends. The kids in Guatemala Urban center are getting regular remittances, and Edelmira's debt is almost paid off. And then Fermina gets pregnant.

When Fermina tin no longer hibernate her pregnancy, she'due south fired from her jobs. A old co-worker puts her in bear upon with an American lesbian couple in Phoenix that has merely adopted two Guatemalan kids.

Information technology's 2007. Fermina has lived in Phoenix for a year. She shares an apartment with Florentin and four other guys and they all sleep on the floor. She knows neither she nor Florentin can feed or clothe their unborn child. Their baby volition accept a better life with the two white women, Fermina decides. Florentin is heartbroken, merely agrees.

The futurity adoptive moms assistance Fermina obtain medical care, put her up in an air-conditioned apartment, feed her nutritious food, and assist her purchase care packages for the 3 kids in Guatemala: apparel, gummy vitamins, school supplies, shoes. One of the adoptive mothers pumps her own breasts every 2 hours for weeks. When her son is born, Fermina puts him on the adoptive mother'south breast, and teaches her how to nurse.

JORGE SHOWS up in Phoenix a few days afterward.

The tortilla concern has failed. Veronica has been deeply lonely. There's no money for her schooling, and the kids in Guatemala Metropolis do a lot of alcohol and drugs. The G-18 gang is a menace. Omar has been getting whiny. Jorge has struggled to keep the siblings safe. When he's 19, he decides to illegally cantankerous into Arizona and join his mom, leaving his younger siblings with relatives in El Porvenir. He doesn't tell Omar he'south leaving.

Cipher goes correct on the trip north. In United mexican states Metropolis, a taxi commuter robs him. Jorge is grateful his female parent taught him to ever sew a hugger-mugger stash of cash in his clothes. Next, the desert crossing is hot and exhausting, fifty-fifty though it's the rainy flavour. In Phoenix, he'south held for ransom past the coyote until Fermina and the women who take adopted Gabriel pay his way out of the drop firm. (Gabriel'south name has been changed to protect his identity.)

Fermina arranges for Veronica and Omar to stay in El Porvenir. They bounce around from business firm to house feeling similar burdens—living with an aunt, and so a grandfather, then a neighbor. Every calendar week, she calls. The kids tell her they're miserable. They miss her cooking, and her snobby affection.

Veronica crosses the Arizona desert with an evangelical coyote in 2008. "Ustedes ya no me quieren"—you all don't love me anymore—Omar tells his mother on the phone. He begs her to bring him to Arizona. Fermina tells Omar to stay put until he finishes sixth class. When he finishes, she tells him to wait until he finishes seventh grade. She'll come up home by then, she says, with money for a farm just like the family unit subcontract in Tuibuj.

So Omar starts cutting classes at his school, Escuela Justo Rufino Barrios. He hangs effectually the schoolyard and makes friends with an older woman who sells tostadas. Her proper noun is Maria Teresa Gonzales Cax, only she is known locally equally Doña Teresa.

In 2010, officials noticed a surge of children crossing the border without their parents or guardians.

A stout 55-year-old woman with short black pilus, Doña Teresa has borrowed besides much money to pay for a house. The debt collector is threatening her; the interest is compounding. She is illiterate and has no way to earn coin, other than making tostadas at her lunch stand. She lives across the street from i of the fine houses built with remittances, and concludes she can pay her debt only if she works in the United States.

Omar has but turned 13. He hasn't seen his mother in four years, his brother in three, and his sister in ii. In his schoolhouse picture, he'due south a minor frowning boy dressed in a crisp white shirt and navy blue pants.

He'due south living with Roxana de Peréz and her husband and kids, right adjacent door to Fermina'southward shack in El Porvenir. (Omar's best friend, Yesmar, is Roxana'due south son.) Fermina sends Roxana $57 monthly for Omar's upkeep, and she sends Omar about $30 each month for schoolhouse snacks and school supplies. Sometimes, Omar plays in his female parent's shack, near the banana trees and coffee plants.

Once, he vows to build his mom a fine house but like the remittance houses in El Porvenir if she lets him come to Arizona with his new friend Doña Teresa. On a different call, Omar says a strange man has started living in Fermina's shack and if she doesn't bring him to Arizona, the human being will kill Omar. Fermina finally relents. She sends Omar and Doña Teresa $800 for the first role of their journey.

Doña Teresa and Omar travel a few miles past omnibus to El Carmen, where the Suchiate River separates Mexico and Guatemala. It'southward a major crossing point for thousands of Primal Americans en route to the United States. The Hotel Arizona is just up the street from the bridge, along with a luggage shop. Street vendors militarist American dollars. Doña Teresa and Omar walk legally across the span with shopping visas. Omar's backpack is weighted downward with the hammer he's bringing to build his mother a house.

The two travelers linger in Tapachula, in the state of Chiapas, Mexico, for almost a month. They stay with Doña Teresa's sister, a Mexican citizen. The sister's husband collapsed on a desert edge crossing into Arizona 10 years before; he was revived by the Border Patrol and ultimately deported. He'd been in the desert three days, and has never been the same.

Fermina and Florentin are getting worried. The desert is getting hotter; why is Doña Teresa dawdling in Tapachula? Doña Teresa says she's having difficulty finding smugglers and ownership imitation Mexican documents for Omar. Those documents will not only assist ensure a condom passage through United mexican states; they volition aid ensure that Doña Teresa and Omar will exist deported to the Mexican line, and not Guatemala, if they're caught by immigration officials in the The states. (Doña Teresa volition use her sister'due south Mexican ID for the journey.) In the meantime, Omar is spending precious travel money at the arcades with his new friends.

In late June, Omar and Doña Teresa lath the omnibus for Altar, Sonora, where they look some other few days while the coyote gathers enough clients to make up a grouping willing to cantankerous the Arizona desert in the triple-digit July heat. Doña Teresa and Omar tell Fermina they have Mexican IDs and at least i backpack. Doña Teresa has packed her prized crocheted collar adorned with fake pearls and garnets. Omar has packed his orangish comb and toothbrush.

IN 2010, the year Doña Teresa and Omar brand their journey, federal immigration officials are taking notice of a new surge of undocumented border-crossers. They're kids, technically called "unaccompanied minors," meaning they cross the border without their parents or legal guardians. Most come from nearby Mexico, but more and more are from Fundamental America. In 2008, the Border Patrol apprehended one,388 unaccompanied Guatemalan kids crossing the southern border illegally. By 2012, that number will have risen to 3,835 kids.

The main reason for this trend, says Cecilia Menjivar, a professor at the T. Denny Sanford School of Social and Family unit Dynamics at Arizona State University, is the desire of kids to exist reunited with parents they haven't seen in years, and "particularly their mothers." The children are ofttimes the instigators of the edge crossings, so, she says, travel plans are "ofttimes haphazard."

On July 6, a coyote phones Fermina. Doña Teresa and Omar are part of a group that will cross into the Arizona desert that night. In a few days, they will arrive in Phoenix, and he volition advise her of the driblet-house location. Jorge buys his niggling brother a videogame.

Several days afterward, the coyote calls Fermina again. On the first mean solar day of the crossing, Doña Teresa could no longer go along up with the grouping and Omar stayed behind with her, he says. Don't worry, he tells Fermina, the Border Patrol will selection them up. They will be fine.

Information technology'south the summer of 2010, and Arizona'south famous immigration law, SB 1070, has been passed. The police force essentially makes it a country crime for unauthorized immigrants to set foot in Arizona, and Sheriff Joe Arpaio is raiding Latino neighborhoods and workplaces in the Phoenix surface area. Every bit a upshot, the undocumented people who have not fled Phoenix, including Fermina, equate police enforcement with immigration enforcement. Fermina is afraid to report her missing son to the cops, because she is scared they might deport her. And so what would she practise if Omar showed up in Phoenix?

Instead, she turns for help to Lydia Guzman, a local immigrant-rights activist in Phoenix, as well as Gabriel'due south two moms, who have moved to Massachusetts considering they fear constabulary enforcement will harass their iii Guatemalan children if they raise them in Arizona.

While Guzman notifies human rights groups, the Pima County Office of the Medical Examiner, the Border Patrol, and the news media, the moms in Massachusetts hound the coyote with telephone calls. He says not to worry: the Border Patrol will find Omar and Doña Teresa. And so he disconnects his phone. Gabriel's adoptive parents plow to immigration officials who deal with unaccompanied minors, cheque shelters, telephone call homo rights groups. They call everyone they can think of, explaining each fourth dimension that Omar had Mexican, not Guatemalan documents.

Fermina talked to the media. It'due south safer to call reporters than cops. Reporters don't enforce immigration laws.

When she isn't working at the juice factory with Florentin, Fermina waits for Omar's call. She talks to print and broadcast media, only doesn't reveal her immigration condition. It's safer to call reporters than cops. Reporters don't enforce immigration laws. She files a missing border-crosser report at the Guatemalan consulate in Phoenix. She tries to file a like written report at the Mexican consulate, but since Omar was using fake Mexican documents, the consulate can't help her.

In Guatemala City, Fermina'southward uncle, Toribio Chilel, notifies the Guatemalan government and homo rights groups. He searches for Omar in the slum where the kids had lived, and in El Porvenir.

The months pass, and still there is no word from Omar. Fermina sits by the phone and prays. She remembers her mother's disappearance and her grandparents' disappearance. She knows God is skillful and wouldn't practise this to her once again.

Each Sunday, at the Iglesia de Dios, she is reminded of God'due south goodness. "We love your presence, nosotros love you God," the band sings. "At that place's life afterwards death." God make a miracle for me, Fermina prays.

After a few months, the media loses involvement in the example. Lydia Guzman and Gabriel's moms continue calling immigration authorities and human rights workers, and Fermina keeps visiting the Guatemalan consulate. Only no one has constitute Omar.

Fermina dreams. In one dream, Omar is tiny and with his father. In another dream, Omar is in a large room with many children. When she awakens, she asks herself: where is the room? In the Usa? In Mexico? Is the room part of a schoolhouse? Or a church building?

Fermina and Florentin brainstorm hearing rumors from other immigrants. Omar is sighted in North Carolina. Doña Teresa is sighted working at a pizzeria in Houston. They're live, Fermina thinks, they've but lost my phone number.

Near A yr after Omar disappears, Veronica gives birth to a son, Daniel. The father leaves Phoenix, fearful of getting swept up in a sheriff'southward raid and being deported. Veronica tracks him downwardly on Facebook, and he'southward on the E Coast. She's struggling with school, having had but three years of education in Guatemala, and though she tries difficult, she can't pass all the standardized tests that lead to a high school diploma.

Fermina and Florentin accommodate their work schedule at the juice factory so that Fermina tin sentry her new grandson while Veronica is in school. "God has blessed y'all with a grandson," Florentin says, trying to make Fermina feel better about Omar'southward disappearance. "It's not the aforementioned, and you know it," Fermina answers.

Every day, she waits for Omar'south phone call. And when he doesn't call, she tells herself that he'll call tomorrow. Every day I idea I'd see my mother's face, she thinks. Now every twenty-four hour period I call up I'll meet Omar's face.

THE Fractional skeletons of a child and older woman are found in the Arizona desert in early 2012. The coroner's part notifies foreign consulates and human rights groups, and they in turn have one report that sounds like a match. It was filed in 2010 past Fermina as well every bit Gabriel's moms and Lydia Guzman, and involves a 13-yr-old boy and a 55-twelvemonth-old woman who crossed the desert in the same area where the skeletons were found.

Three months after the bones are discovered, Fermina is called into the Guatemalan consulate in Phoenix. Her mouth is swabbed for a DNA sample, to see if her DNA matches the Dna of the basic found in the desert. She sees pictures of the skeletal remains and the false teeth with the star. She weeps at commencement, then tells herself the basic cannot be Omar's because she knows he is alive. She calls Doña Teresa's family in El Porvenir, and they say the simulated teeth don't vest to their relative. Secretly, Doña Teresa'south family believes she is alive besides, hiding out in United mexican states or the United States because Omar has vanished while under her care and she fears she will be arrested.

3 weeks after Fermina gives her Dna sample, the Guatemalan consulate tells her there's a very strong run a risk that the skeleton belongs to Omar, just scientists desire to examination the Deoxyribonucleic acid of Omar'due south father as well. In August, Fermina buys Omar'due south dad a bus ticket to travel to Guatemala City so authorities can swab his mouth for a Deoxyribonucleic acid sample.

Some other Christmas passes without Omar. So another Easter. It's early on April 2013 when Fermina and Florentin are summoned to the Guatemalan consulate in Phoenix.

In the waiting room, they sit together on chairs nigh walls covered with posters that warn of the dangers of crossing the desert. Para el coyote es cosa de suerte. Para ti es cosa de muerte, i sign warns. (For the coyote it's a matter of luck. For you it's a matter of expiry.) Cada día mueren tres personas en la frontera nunca es el coyote. (Every day, 3 people die on the border and it'due south never the coyote.)

Vice-Delegate Carlos de León summons the ii into his office, where a pastor and his married woman expect them. The vice-consul has arranged a joint Skype phone call with Doña Teresa'due south family in Guatemala, and a fellow member of the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Squad, which has helped with the DNA testing. The skeletal remains of Maria Teresa Gonzales Cax and Nelson Omar Chilel Lopez have been positively identified. Fermina breaks downwards, and the pastor tells her to trust in God. At least the search for Omar is over, the pastor says.

At the Office of the Pima County Medical Examiner on Apr 16, Dr. Gregory Hess closes out his reports. He tin can't exist sure, only he suspects Doña Teresa and Omar died of heat exposure. After the group left them, they likely lay down below the tree for scant shade. As their body temperatures rose, their cellular functions shut down. One by one, or perhaps together, they became flushed, nauseated, drawn. They may have get febrile. They were non necessarily in pain, but probable uncomfortable. Then they passed out and died.

FERMINA AND Florentin at present live together on the w side of Phoenix, in a firm they share with two other Guatemalan immigrants. Near the front door, in that location is a sign made of yellow-brown plastic autumn leaves that says, "Welcome!" In the backyard, Fermina steams the tamales she still sells door-to-door each weekend.

I had met Fermina for the offset time in January of this twelvemonth, several months earlier she would receive the results of the final Dna test. (I asked to see her afterwards Lydia Guzman—the activist who had reunited dozens of missing migrants with their families—told me this was the one instance she had been unable to solve.) Over the adjacent few months, I visit Fermina nearly in one case every two or three weeks, and meet and speak with many of the people who have played a role in her story—including her children, Florentin, one of Gabriel'southward moms, and her relatives and neighbors in El Porvenir.

When I visit Fermina in May, she sits at a table holding a Kleenex. She's about five feet alpine, with long black pilus that hangs to her knees when information technology's not braided. She'due south 47 now, with a wide-prepare confront and dark, sorry eyes. She wears a jean-skirt that is virtually down to her ankles, a flowered blouse, and sandals. Her grandson begs for attention; she tears off a piece of corn tortilla, sprinkles information technology with common salt, and absently easily it to him.

"Why did this happen?" she wails to Florentin, who sits on the couch.

"Hundreds cantankerous the desert," she says. "Omar had food and water. Did Doña Teresa make him stay with her? Did he die of heat? Did he dice of thirst? How did he die?"

"In that location are and then many questions," Florentin says, looking down at his nails stained pink from juice concentrate. "Nosotros have no answers."

She looks at a bag of fresh cherries on the table. She says, "Omar never tasted a ruddy." If her mother had not disappeared, she says, she could have left the kids with her and none of this would have happened.

OMAR AND Doña Teresa take papers for their last journey. Their remains are transported from Tucson to a funeral home in Phoenix, where they are placed as delicately as possible in separate metal boxes. From Phoenix the small boxes are flown to Dallas. On June 14, they are loaded onto American Airlines Flight 2137 jump for Republic of guatemala Urban center. I am on the same plane, because I am traveling to Guatemala to nourish Omar's wake and burying.

Uncle Toribio is waiting at the airport for Omar's body when it arrives in Republic of guatemala Urban center. He helps a funeral-home official transfer the airtight metallic box into a large silver catafalque busy with metalwork depicting the Last Supper and angels. He watches every bit the casket is loaded into a white hearse, so climbs in beside it for the seven-hour bulldoze to El Porvenir.

In El Porvenir, neighbors and relatives greet the hearse at the bottom of a loma and have turns carrying the casket up the steep stone-and-dirt road to Fermina's shack. It'southward raining, and the shack is in a sad state of disrepair, but someone has anchored plastic sheeting with rocks on meridian of the roof to try to go along it dry out.

The shack has been turned into an chantry. The silver casket is lowered onto a stand and framed with lace curtains. Someone puts Omar's school moving-picture show on height of the casket. There's a plastic salad bowl for donations to help defray funeral expenses, but in truth the entire $i,500 funeral has been prepaid past Fermina, who has micromanaged arrangements from her cellphone in Phoenix. This is her final act of long-altitude mothering, and she wants it to be perfect. She tin't gamble going to the funeral, because she has no papers to return to the United states of america. (Her fearfulness of not getting dorsum into the U.S., where Jorge and Veronica at present live, eclipses her fright of being deported: Arpaio is no longer raiding neighborhoods and workplaces, cheers to judicial decisions and federal immigration policies that accept curbed his enforcement power.)

Over the phone in Phoenix, Fermina has bundled for twenty beige plastic chairs to make full her shack. Outside, 2 patched tarps cover about lxxx more plastic chairs, and speakers blare the same high-decibel praise music that Fermina hears in her church.

Fermina's father, Alberto, sits on 1 of the plastic chairs and stares at his grandson's coffin. He's a pocket-sized, sparse, expressionless man dressed in a dark-green shirt and dark-brown slacks. He didn't know Omar was leaving; no 1 informed him, and he would have stopped information technology, he tells me. Thank God they found him, he says. He stays with the coffin all nighttime.

His family has scattered. Fermina, Rosendo, Lucia, and Clarissa are all in the United States. Merely Romelia remains in El Porvenir.

Marco Antonio Luis Mendez, a 52-year-old pastor, tells me that he knew Omar his whole life. "He lost his life because of poverty," he says. "Fermina struggled for her kids without a man to help her." The male child went to Arca de Salvación church every Sunday. Not all kids are as expert as he was; not anymore. They steal and do drugs and are disrespectful. "Outset nosotros were afraid of the regular army and the guerrillas," Marco tells me, "and at present we're afraid of the kids."

The official pastor comes effectually ix p.thousand. He talks about Lazarus. He sings a vocal near leaving the Earth and being in the artillery of the Savior. He talks well-nigh the boy "who isn't here" but is within the casket and how he accepted God and how the lives of immigrants carry dandy peril.

A few blocks away, the family of Doña Teresa stands before a coffin in a like altar. In that location's a motion-picture show of Doña Teresa wearing her favorite blue apparel, and a tub of flowers. "People said they'd seen her in Chicago," says her son Gilberto. "She was illiterate and we idea she'd lost our phone number and couldn't go far bear on with us … Thank God they've found her and brought her home."

THE Adjacent day is sunny, and the air smells of cooking fires. The mortuary officials arrive nearly noon and place the tubs of flowers and paper wreaths in the back of their pickup truck, which blares praise music from four speakers.

Carefully, Omar's uncles and aunts and cousins and friends take turns carrying the bury through the streets of El Porvenir. The older women wear their Mayan clothes and shade themselves from the hot sun with colorful umbrellas. When the praise music stops looping for i or two seconds, yous can hear the sound of their sandals hitting the stone streets.

The procession gathers mourners every bit it moves frontward, past the plaza and the street where Omar was born, past the open-air market selling chilies and shoes and bananas, past the soccer field and schoolhouse. The mourners wind out of boondocks, down a hill and over a bridge, where below on the river women wash apparel on rocks. Vendors race alee, selling common cold juices, sweet rolls, and salty snacks every bit the procession passes, then race alee again, tinkling their hand-held bells.

At the bottom of the hill, there's a sign that says "Happy Travels." The procession passes two children with machetes, grazing horses, and an erstwhile man carrying wood on his dorsum. Later two kilometers, the procession enters the cemetery. The expressionless are not cached underground here. Instead, the caskets are sealed in above-ground cement tombs.

The silver casket is placed on meridian of its concrete tomb, and suddenly Fermina's vocalization blares over the truck's speakers. She'southward calling from her cellphone in Phoenix. "Cheers," she says, "for honoring my son and supporting my family. There are no words to express my gratitude."

As Granddaddy Alberto watches, Rufino and Romelia and younger family members slide the bury into its physical tomb, and Marco Antonio Luis Mendez says Omar has gone to Jesus. The women wail. Uncle Rufino mixes a bag of cement with water and seals the tomb.

Information technology'S JULY 2013, iii years later on Omar disappeared crossing the border. In Washington, the debate about the immigration bill rages. Almost of the opposition comes from those who say that the nib is besides lenient toward undocumented immigrants. Few seem to find or care that the neb'southward "edge surge" will almost certainly mean more deaths like Omar'southward.

Meanwhile in Phoenix, Fermina can't forgive herself. She wonders if God took away Omar as punishment for giving away her son Gabriel to the two moms in Massachusetts. Or maybe God is punishing her because she was stupid enough to give Omar the money to come north. "I killed my son," she ofttimes says.

Fermina at present lives merely for Jorge, who is 24, and Veronica, who is xx. Veronica wants to be an auto mechanic merely Fermina insists she stay in school. Information technology's terrible to exist illiterate, she tells Veronica, terrible to exist uneducated. Once she gets Veronica through school, maybe she'll return to El Porvenir and die at that place.

In Republic of guatemala, the basic of the disappeared are reappearing as mass graves are uncovered. With each new homo rights trial, such as the recent genocide trial of former President Efraín Ríos Montt, there's new documentation of massacres and abuses, new hints of locations of bones. Fermina found Omar through DNA testing; maybe she can find the basic of her female parent and grandparents through DNA too, she tells me. If she does, she wants to bury them in the cemetery at the bottom of the hill, near Omar.

rothermelhicely1965.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.newsweek.com/2013/07/10/death-desert-immigration-reform-killing-american-dream-237702.html

0 Response to "Guatemalan Immigrant Kills a Family With a Hammer"

Postar um comentário